Arthur C Clarke

Biography

Arthur C. Clarke’s legacy bridges the worlds of the arts and the sciences. His work ranged from scientific discovery to science fiction, from technical application to entertainment. As an engineer, as a futurist, and as a humanist, Clarke has influenced numerous artists, scientists, and engineers working today, and through his broad body of work, and through the organizations keeping his legacy alive like the Clarke Foundation and this Institute, he continues to inspire future generations around the world. In Memoriam, Neil McAleer, Sir Arthur’s only authorized biographer.

His Life

Arthur Charles Clarke was born to an English farming family in the seaside town of Minehead, in the county of Somerset in southwestern England, on December 16, 1917. As a child, he enjoyed stargazing and reading American science fiction magazines, which sparked his lifelong enthusiasm for space sciences. After moving to London in 1936, Clarke was able to pursue his interest further by joining the British Interplanetary Society (BIS.) He worked with astronautic material in the Society, contributed to the BIS Bulletin, and began writing science fiction

After World War II erupted in 1939, Arthur Clarke joined the Royal Air Force and served as a radar instructor and technician from 1941 to 1946. He was an officer in charge of the first radar talk-down equipment, the Ground Controlled Approach, during its experimental trials. The technique is used by aircraft control to guide aircraft to a safe landing based on radar images during inclement weather. Clarke’s only non-science-fiction novel, Glide Path, was based on his experiences in this project. After the war, Clarke returned to London, where he was awarded a Fellowship at King’s College, London, where he obtained a first class honors degree in Physics and Mathematics in 1948. He also returned to the British Interplanetary Society, and served as the Society’s president in 1946-47 and 1951-1953.

Clarke moved to Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) in 1956, largely to pursue his interest in underwater exploration along the country’s coast as well as on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. He lived first in the coastal village of Unawatuna and then in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s largest city. In 1962, Clarke was diagnosed with polio, which reduced his diving activities. In 1988, he was diagnosed with post-polio syndrome, and he was largely confined to a wheelchair until he passed away at the age of 90 on March 19, 2008.

Arthur Clarke’s remarkable lifetime work was recognized by both the country of his birth and his adopted home country. In 1988, Queen Elizabeth II honored Clarke with a Knighthood, formally conferred by Prince Charles in Sri Lanka two years later. In 2005, Clarke was awarded Sri Lankabhimanya (The Pride of Sri Lanka), Sri Lanka’s highest civilian honor.

Arthur C. Clarke, the Engineer

Arthur Clarke’s experiences during World War II and education in physics and mathematics made him well poised to make significant contributions in engineering after the war. In 1945, Clarke published his landmark scholarly paper “Extra-Terrestrial Relays – Can Rocket Stations Give World-wide Radio Coverage?” in the British magazine Wireless World (download PDF). In the paper, Clarke set out the first principles of global communication via satellites placed in geostationary orbits. A geostationary satellite orbits the Earth above the equator so that the period of the orbit (the time it takes the satellite to complete one orbit around the Earth) is the same as the Earth’s rotational period (the time it takes the Earth to rotate once around its axis.) This means that to an observer located on the surface of the Earth, the satellite appears not to move in the sky but stay at a fixed position. The idea of these kinds of orbits was originally proposed in 1928, but Clarke was the first to suggest that geostationary orbits would be ideal for establishing worldwide telecommunication relays. Since a satellite in a geostationary orbit does not appear to move in the sky, antennas on the ground do not have to track the satellite across the sky but can be pointed permanently to one location, which makes communications between ground stations and satellites easier.

Over the next decades, Clarke’s discovery evolved from his original, pre-computer era idea of using large, manned space stations to act as relays, to the small, unmanned, robotic telecommunications satellites used today. During this time, Clarke worked with scientists and engineers in the United States in the development of spacecraft and launch systems. After the launch of the Sputnik satellite by the Soviet Union in 1957, the discussion of the use of outer space by different nations of the Earth become an important global issue. Clarke was involved in these discussions by, e.g., addressing the United Nations during their deliberations on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. In the 1950s, Clarke started corresponding with Dr. Harry Wexler, the chief of the Scientific Services Division of the U.S. Weather Bureau, about satellite applications for weather forecasting. These discussions led to Dr. Wexler being the leading force behind a new branch of meteorology, where rockets and satellites were used for meteorological research and operations. Clarke saw his vision of global telecommunications via satellites start to become reality in 1964 with the launch of the first geostationary communication satellite Syncom 3, which was used to broadcast the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo to the United States. Today’s world relies so heavily on global satellite telecommunications networks that it would be difficult to imagine what the world would look like without them.

Arthur Clarke’s engineering work brought him numerous awards and honors, including the 1982 Marconi International Fellowship, a gold medal of the Franklin Institute, the Vikram Sarabhai Professorship of the Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, the Lindbergh Award, and a Fellowship of King’s College, London. Today, the geostationary orbit at 36,000 kilometers (22,000 miles) above the equator, which Clarke first described as useful for satellite communication relays, is named the Clarke Orbit by the International Astronomical Union.

Arthur C. Clarke, the Futurist

As important as Arthur Clarke’s achievements in engineering were to the modern world, he is at least as well known as a futurist, trying to predict what the world of tomorrow might look like, and as a popularizer of science, helping make science accessible to everyone. He is perhaps best known as a world-renowned science fiction writer, starting with the first story he sold professionally, “Rescue Party”, which was written in March 1945 and appeared in the magazine Astounding Science in May 1946. His body of work contains more than 70 books of fiction and non-fiction, and he received numerous awards for his writing.

Clarke’s most famous non-fiction work as a futurist may be the book Profiles of the Future, based on a series of essays he started writing in 1958 and published in book form in 1962. In the book he envisioned the probable shape of tomorrow’s world, including a timetable of possible inventions from the present to the year 2100. He often incorporated his visions of the technological advances in the near future into his science fiction writing. A prime example of this is his 1979 novel Fountains of Paradise, which describes the construction of a space elevator, a giant structure rising from the ground and linking with a satellite in a geostationary orbit. While concepts for various kinds of space elevators had been discussed for decades, Clarke helped bring the idea to the larger public consciousness and envisioned a future where the use of space elevators to lift payloads to orbit would make rocket launches obsolete.

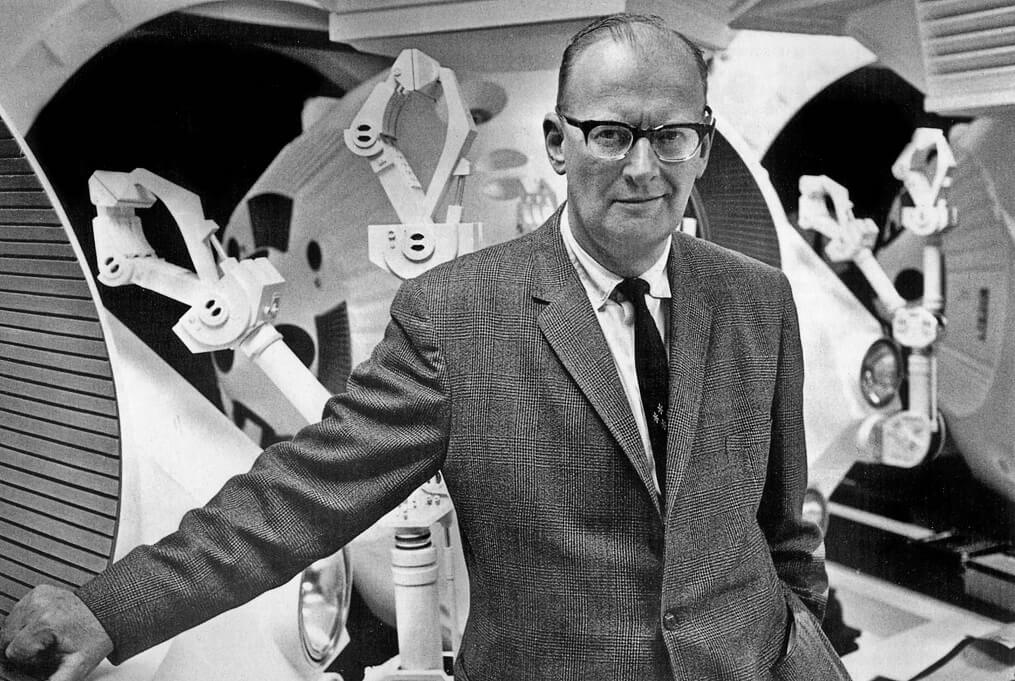

Clarke strived to engage audiences in different media. In 1964, he started working with the noted film producer Stanley Kubrick on a science fiction movie script. The result of the collaboration was the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was released in 1968 and is widely recognized as one of the most influential films ever made. Clarke and Kubrick were nominated for the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award for the film. Clarke also wrote a novelization of the film; the resulting book, which is based on the early drafts of the film and differs from it in some ways, also came out in 1968. Clarke published a sequel, 2010: Odyssey Two, in 1982, and worked with director Peter Hyams on the movie version, which was released two years later. One of the notable aspects of this collaboration was the very advanced way (for the time) it was done: using a Kaypro computer and a modem to link Arthur Clarke in Sri Lanka and Peter Hyams in Los Angeles. This novel approach was described later in the book The Odyssey File – The Making of 2010.

Clarke worked for decades in television, bringing scientific and engineering achievements to people’s homes across the world. He worked alongside Walter Cronkite and Wally Schirra for the CBS coverage of the Apollo 12 and 15 space missions in the United States. His TV series Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World (1981), Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers (1984), and Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious Universe (1994) have been shown in many countries around the world. Clarke also contributed to other TV series about space, such as Walter Cronkite’s Universe series in 1981.

Arthur C. Clarke, the Humanist

Arthur Clarke was always interested in the future of human race, not only in terms of what that future might look like, technologically speaking, but also in terms of what kind of a world we, the current inhabitants of our home planet, would leave to the future generations. As a result, Clarke was always concerned about the relationship of the human race to the natural world around it.

An expression of Clarke’s interest in the interaction of humans with nature was his enthusiasm for scuba diving. Clarke’s undersea explorations connected the purely personal enjoyment of the activity to history of the areas he explored. For example, in 1956 he discovered the underwater ruins of the original Koneswaram temple in Trincomalee, Sri Lanka, during a scuba diving expedition with the photographer Mike Wilson.

Clarke was devoted to making sure the next generation would receive the best education possible. He not only influenced young minds through his writing but also worked in formal education. He served as the Chancellor of the Moratuwa University in Sri Lanka in 1979-2002 and as the first Chancellor of the International Space University in 1989-2004.

Clarke was concerned about global climate change and what effect it may have on the future of humanity. He always stressed the urgent need for humanity to move beyond the use of fossil fuels, which he considered one of our most self-destructive behaviors. Yet Clarke was always optimistic about the future of humanity; he firmly believed that technological achievements would solve our current problems and lead to a better and brighter future for the entire human race.

It is Clarke’s optimism for the future that made him an ideal spokesperson for the importance of people across the globe working together to solve the problems of today and create a better world for all of humanity. The organizations carrying Clarke’s name, from the Arthur C. Clarke Foundation to the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Science Education, are proud to continue Clarke’s legacy of inspiring the present and future generations of Earth, our home planet.

I’m sometimes asked how I would like to be remembered. I’ve had a diverse career as a writer, underwater explorer, space promoter and science populariser. Of all these, I want to be remembered most as a writer — one who entertained readers, and, hopefully, stretched their imagination as well.—Arthur C. Clarke

Quotes

Sir Arthur’s Quotes

In the struggle for freedom of information, technology, not politics, will be the ultimate decider.

Every revolutionary idea seems to evoke three stages of reaction. They may be summed up by the phrases: (1) It’s completely impossible. (2) It’s possible, but it’s not worth doing. (3) I said it was a good idea all along.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

As our own species is in the process of proving, one cannot have superior science and inferior morals. The combination is unstable and self-destroying.

Human judges can show mercy. But against the laws of nature, there is no appeal.

I don’t pretend we have all the answers. But the questions are certainly worth thinking about.

It has yet to be proven that intelligence has any survival value.

It is not easy to see how the more extreme forms of nationalism can long survive when men have seen the Earth in its true perspective as a single small globe against the stars.

It may be that our role on this planet is not to worship God but to create him.

Our lifetime may be the last that will be lived out in a technological society.

Politicians should read science fiction, not westerns and detective stories.

I don’t believe in astrology; I’m a Sagittarius and we’re skeptical.

The best measure of a man’s honesty isn’t his income tax return. It’s the zero adjust on his bathroom scale.

The greatest tragedy in mankind’s entire history may be the hijacking of morality by religion.

The limits of the possible can only be defined by going beyond them into the impossible.

There is hopeful symbolism in the fact that flags do not wave in a vacuum.

This is the first age that’s ever paid much attention to the future, which is a little ironic since we may not have one.

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

The best proof that there’s intelligent life in outer space is the fact that it hasn’t come here.

We stand now at the turning point between two eras. Behind us is a past to which we can never return … The coming of the rocket brought to an end a million years of isolation … the childhood of our race was over and history as we know it began.

The fact that we have not yet found the slightest evidence for life — much less intelligence — beyond this Earth does not surprise or disappoint me in the least. Our technology must still be laughably primitive; we may well be like jungle savages listening for the throbbing of tom-toms, while the ether around them carries more words per second than they could utter in a lifetime.

Two possibilities exist: Either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.

The Information Age offers much to mankind, and I would like to think that we will rise to the challenges it presents. But it is vital to remember that information — in the sense of raw data — is not knowledge, that knowledge is not wisdom, and that wisdom is not foresight. But information is the first essential step to all of these.

There is hopeful symbolism in the fact that flags do not wave in a vacuum.

I can never look now at the Milky Way without wondering from which of those banked clouds of stars the emissaries are coming. If you will pardon so commonplace a simile, we have broken the glass of the fire alarm and have nothing to do but to wait. I do not think we will have to wait for long.

—The Sentinel, 1948

Yet now, as he roared across the night sky toward an unknown destiny, he found himself facing that bleak and ultimate question which so few men can answer to their satisfaction. What have I done with my life, he asked himself, that the world will be poorer if I leave it.

—Glide Path, 1963

Behind every man now alive stand thirty ghosts, for that is the ratio by which the dead outnumber the living.

—Foreword to 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968

One of the biggest roles of science fiction is to prepare people to accept the future without pain and to encourage a flexibility of mind. Politicians should read science fiction, not westerns and detective stories.

—The Making of Kubrick’s 2001, Jerome Agel, 1970

Any teacher that can be replaced by a machine should be!

—Electronic Tutors, 1980

The dinosaurs disappeared because they could not adapt to their changing environment. We shall disappear if we cannot adapt to an environment that now contains spaceships, computers — and thermonuclear weapons.

—The Collected Stories, 2000

The danger of asteroid or comet impact is one of the best reasons for getting into space … I’m very fond of quoting my friend Larry Niven: “The dinosaurs became extinct because they didn’t have a space program. And if we become extinct because we don’t have a space program, it’ll serve us right!”

—Meeting of the Minds : Buzz Aldrin Visits Arthur C. Clarke, Andrew Chaikin, 2001

SETI is probably the most important quest of our time, and it amazes me that governments and corporations are not supporting it sufficiently.

—Seti@Home, 2006

2001 was written in an age which now lies beyond one of the great divides in human history; we are sundered from it forever by the moment when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped out on to the Sea of Tranquility. Now history and fiction have become inexorably intertwined.

—Foreword to the Millennial Edition of 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1999

… we have a situation in which millions of vehicles, each a miracle of (often unnecessary) complication, are hurtling in all directions under the impulse of anything up to two hundred horsepower. Many of them are the size of small houses and contain a couple of tons of sophisticated alloys – yet often carry a single passenger. They can travel at a hundred miles an hour, but are lucky if they average forty. In one lifetime they have consumed more irreplaceable fuel than has been used in the whole previous history of mankind. The roads to support them, inadequate though they are, cost as much as a small war; the analogy is a good one, for the casualties are on the same scale.

—Profiles of the Future, 1972

For his 90th birthday in December 2007, Arthur C. Clarke recorded a greeting to his friends around the world. As part of the message, Clarke expressed three wishes:

Firstly, I would like to see some evidence of extra-terrestrial life. I have always believed that we are not alone in the universe. But we are still waiting for ET to call us — or give us some kind of a sign. We have no way of guessing when this might happen — I hope sooner rather than later!

Secondly, I would like to see us kick our current addiction to oil, and adopt clean energy sources. … Climate change has now added a new sense of urgency. Our civilisation depends on energy, but we can’t allow oil and coal to slowly bake our planet…

The third wish is one closer to home. I’ve been living in Sri Lanka for 50 years — and half that time, I’ve been a sad witness to the bitter conflict that divides my adopted country. I dearly wish to see lasting peace established in Sri Lanka as soon as possible.

In his 90th birthday message, Clarke also addressed his legacy:

I’m sometimes asked how I would like to be remembered. I’ve had a diverse career as a writer, underwater explorer, space promoter and science populariser. Of all these, I want to be remembered most as a writer — one who entertained readers, and, hopefully, stretched their imaginations as well.

From Profiles of the Future, 1973 Edition

Our age is in many ways unique, full of events and phenomena that never occurred before and can never happen again. They distort our thinking, making us believe that what is true now will be true forever, though perhaps on a larger scale. Because we have annihilated distance on this planet, we imagine that we can do it once again. The facts are otherwise, and we will see them more clearly if we forget the present and turn our minds towards the past.

When the pioneers and adventurers of our past left their homes in search of new lands, they said good-bye forever to the place of their birth and the companions of their youth. Only a lifetime ago, parents waved farewell to their emigrating children in the virtual certainty that they would never meet again. And now, within one incredible generation, all this has changed.

We have abolished space here on the little Earth; we can never abolish the space that yawns between the stars. Once again, as in the days when Homer sang, we are face-to-face with immensity and must accept its grandeur and terror, its inspiring possibilities and its dreadful restraints.

To obtain a mental picture of the distance to the nearest star, as compared with the distance to the nearest planet, you must imagine a world in which the closest object to you is only five feet away — and there is nothing else to see until you have traveled a thousand miles.

Space can be mapped and crossed and occupied without definable limit; but it can never be conquered. When our race has reached its ultimate achievements, and the stars themselves are scattered no more widely than the seed of Adam, even then we shall still be like ants crawling on the face of the Earth. The ants have covered the world, but have they conquered it — for what do their countless colonies know of it, or of each other? So it will be with us as we spread out from Mother Earth, loosening the bonds of kinship and understanding, hearing faint and belated rumors at second — or third — or thousandth hand of an ever-dwindling fraction of the entire human race. Though the Earth will try to keep in touch with her children, in the end all the efforts of her archivists and historians will be defeated by time and distance, and the sheer bulk of material. For the numbers of distinct human societies or nations, when our race is twice its present age, may be far greater than the total number of all the men who have ever lived up to the present time. We have left the realm of comprehension in our vain effort to grasp the scale of the universe; so it must always be, sooner rather than later.

Originally from the essay Space and the Spirit of Man, 1965

Verified in Greetings, Carbon-Based Bipeds!, Collected Essays 1934-1998, St. Martin’s Press 1999

We seldom stop to think that we are still creatures of the sea, able to leave it only because, from birth to

death, we wear the water-filled space suits of our skins.

…we cannot predict the new forces, powers, and discoveries that will be disclosed to us when we reach the other planets or can set up new laboratories in space. They are as much beyond our vision today as fire or electricity would be beyond the imagination of a fish.

The rash assertion that ‘God made man in His own image’ is ticking like a time bomb at the foundations of many faiths, and as the hierarchy of the universe is disclosed to us, we may have to recognize this chilling truth: if there are any gods whose chief concern is man, they cannot be very important gods.

From The Light of Other Days, by Arthur C. Clarke and Stephen Baxter, 2000

What we need is a machine that will let us see the other guy’s point of view.

Science demands patience.

What is becoming more interesting than the myths themselves has been the study of how the myths were constructed from sparse or unpromising facts—indeed, sometimes from no facts—in a kind of mute conspiracy of longing, very rarely under anybody’s conscious control.

Just as the human memory is not a passive recorder but a tool in the construction of the self, so history has never been a simple record of the past, but a means of shaping peoples.

The vendors seemed comical, so intent were they on their slivers of meaningless profit, all unaware of the desolate ages that lay in their own near future, their own imminent deaths.

Maybe those nihilist philosophers are right; maybe this is all we can expect of the universe, a relentless crushing of life and spirit, because the equilibrium state of the cosmos is death…

We always thought the living Earth was a thing of beauty. It isn’t. Life has had to learn to defend itself against the planet’s random geological savagery.

Sir Arthur’s Work

Fiction

- Across the Seas of Stars

- Against the Fall of Night

- Childhood’s End

- City and the Stars

- The Deep Range

- Dolphin Island

- Earthlight

- Expedition to Earth

- A Fall of Moondust

- The Fountains of Paradise

- From the Oceans, from the Stars

- Ghosts from the Grand Banks

- Glide Path

- The Hammer of God

- Imperial Earth

- Islands in the Sky

- The Lion of Comarre

- The Lost Worlds of 2001

- The Nine Billion Names of God

- The Other Side of the Sky

- Prelude to Mars

- Prelude to Space

- Reach for Tomorrow

- Rendezvous with Rama

- The Sands of Mars

- The Sentinel

- The Songs of Distant Earth

- The Sentinel

- Tales from the “White Hart”

- Tales of Ten Worlds

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (With Stanley Kubrick)

- 2010: Odyssey Two

- 2061: Odyssey Three

- 3001: The Final Odyssey

- The Wind from the Sun

Non-fiction

- “Extraterrestrial Relays” in Wireless World

- “Space Stations for Global Communications” in Wireless World

- Ascent to Orbit: A Scientific Autobiography

- Astounding days: A Science Fictional Autobiography

- Boy Beneath the Sea

- The Challenge of the Sea

- The Challenge of the Spaceship

- The Coast of Coral

- The Coming of the Space Age (edited)

- The Exploration of the Moon

- The Exploration of Space

- The First Five Fathoms

- Going into Space

- How the World Was One

- Indian Ocean Adventure

- Indian Ocean Treasure

- Interplanetary Flight

- The Making of a Moon

- 1984: Spring

- Profiles of the Future

- The Promise of Space

- The Reefs of Taprobane

- Report on Planet Three

- Science Fiction Hall of fame, III (edited)

- Three for Tomorrow (edited)

- Time Probe (edited)

- Treasure of the Great Reef

- The View from Serendip

- Voice Across the Sea

- Voices from the Sky

Collaborative Works

- With Simon Welfare and John Fairley: Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World; Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers

- With the Astronauts: First on the Moon

- With Robert Silverberg: Into Space

- With Chesley Bonestell: Beyond Jupiter

- With the Editors of Life: Man and Space

- With Peter Hyams: The Odyssey Fil

- With Gentry Lee: Cradle

- With Gentry Lee: Rama 11

Others on Sir Arthur

Arthur C. Clarke is one of the true geniuses of our time.

—Ray Bradbury, American fantasy, horror, science fiction, and mystery writer

Not since George Orwell wrote 1984 has one writer’s name conjured more speculation and fascination with a year than the author of 2001: A Space Odyssey. That writer is, of course, Sir Arthur C. Clarke. He is, at 83, perhaps the most influential science fiction writer in the universe.

—Tom Hanks, American actor, producer, writer, and director.

Nobody has done more in the way of enlightened prediction than Arthur C. Clarke.

—Isaac Asimov, Russian-American author and professor of biochemistry at Boston University

He has done an enormous global service in preparing the climate for serious human presence beyond the Earth.

—Carl Sagan, American astronomer, astrophysicist, cosmologist, author, science popularizer, and science communicator in astronomy and natural sciences

In a world filled with despair and fear, Arthur C. Clarke has always come down on the side of human possibility against the forces of impossibility.

—Alvin Toffler, American writer and futurist

Arthur literally made my Star Trek idea possible, including the television series, the films, and the association and learning it has made possible for me.

—Gene Roddenberry, American television screenwriter, producer and futurist

Arthur somehow manages to capture the hopeless but admirable human desire to know things that can really never be known. … As an artist, his ability to impart poignancy to a dying ocean or an intelligent vapor is unique. He has the kind of mind of which the world can never have enough, an array of imagination, intelligence, knowledge, and a quirkish curiosity which often uncovers more than the first three qualities.

—Stanley Kubrick, American film director, screenwriter, producer, and cinematographer

Arthur C. Clarke, distinguished author of science and fiction, says ideas often have three stages of reaction–first, ‘it’s crazy and don’t waste my time.’ Second, ‘it’s possible, but it’s not worth doing.’ And finally, ‘I’ve always said it was a good idea.’

—Ronald Reagan, 40th President of the United States, 33rd Governor of California, and a radio, film and television actor.

2001 is not just another science-fiction novel or movie. It is a science-fiction milestone–one of the best novels in the genre and undoubtedly the best s.f. movie ever made. …Arguably, Sir Arthur (he was knighted in 1998) has done more than anyone in the 20th century to explain science to the multitude.

—Gerald Jonas, book reviewer, The New York Times

Sir Arthur Clarke has been an inspiration to me since he wrote his first books in the 1940s. I thank him for leading us through the 20th century and guiding us to the heavens.

—Daniel Goldin, NASA Administrator

Sir Arthur Clarke is the Jules Verne of space.

—Jean-Michel Cousteau, French explorer, environmentalist, educator, and film producer.

It has been a great privilege to be a friend of an individual who has made such important contributions to the extraordinary scientific/technical achievements of the 20th century and beyond.

—Walter Cronkite, American broadcast journalist

I count myself among the millions who have been inspired and encouraged by Arthur C. Clarke’s contributions to literature, and I count myself among his many friends.

—Neil Armstrong, American former astronaut, test pilot, aerospace engineer, university professor, United States Naval Aviator, and the first person to set foot upon the Moon

Arthur’s cultural and philosophical contributions to space have been immeasurable, and I want to bring all the thanks from all the Apollo astronauts.

—Buzz Aldrin, American mechanical engineer, retired United States Air Force pilot and astronaut who was the lunar module pilot on Apollo 11 and the second human being to set foot on the moon

You are deservedly the best known science fiction writer in the world. You have done more than anyone to give us a vision of mankind reaching out from cradle Earth to our future in the stars.

—Stanley Kubrick

To Arthur C Clarke – who inspired my summer vacation on Mars.

—Donna Shirley, former manager of Mars Exploration at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

His intellectual sweep, his brilliance, perhaps even more the deep humanity that he has shown, will remain with us for a long time. He is a seer of modern science.

—Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, after Sir Arthur had delivered the Nehru Memorial Address in New Delhi, November 1986

Regular Layout

Biography

Arthur C. Clarke’s legacy bridges the worlds of the arts and the sciences. His work ranged from scientific discovery to science fiction, from technical application to entertainment. As an engineer, as a futurist, and as a humanist, Clarke has influenced numerous artists, scientists, and engineers working today, and through his broad body of work, and through the organizations keeping his legacy alive like the Clarke Foundation and this Institute, he continues to inspire future generations around the world.

His Life

Arthur Charles Clarke was born to an English farming family in the seaside town of Minehead, in the county of Somerset in southwestern England, on December 16, 1917. As a child, he enjoyed stargazing and reading American science fiction magazines, which sparked his lifelong enthusiasm for space sciences. After moving to London in 1936, Clarke was able to pursue his interest further by joining the British Interplanetary Society (BIS.) He worked with astronautic material in the Society, contributed to the BIS Bulletin, and began writing science fiction

After World War II erupted in 1939, Arthur Clarke joined the Royal Air Force and served as a radar instructor and technician from 1941 to 1946. He was an officer in charge of the first radar talk-down equipment, the Ground Controlled Approach, during its experimental trials. The technique is used by aircraft control to guide aircraft to a safe landing based on radar images during inclement weather. Clarke’s only non-science-fiction novel, Glide Path, was based on his experiences in this project. After the war, Clarke returned to London, where he was awarded a Fellowship at King’s College, London, where he obtained a first class honors degree in Physics and Mathematics in 1948. He also returned to the British Interplanetary Society, and served as the Society’s president in 1946-47 and 1951-1953.

Clarke moved to Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) in 1956, largely to pursue his interest in underwater exploration along the country’s coast as well as on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. He lived first in the coastal village of Unawatuna and then in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s largest city. In 1962, Clarke was diagnosed with polio, which reduced his diving activities. In 1988, he was diagnosed with post-polio syndrome, and he was largely confined to a wheelchair until he passed away at the age of 90 on March 19, 2008.

Arthur Clarke’s remarkable lifetime work was recognized by both the country of his birth and his adopted home country. In 1988, Queen Elizabeth II honored Clarke with a Knighthood, formally conferred by Prince Charles in Sri Lanka two years later. In 2005, Clarke was awarded Sri Lankabhimanya (The Pride of Sri Lanka), Sri Lanka’s highest civilian honor.

Arthur C. Clarke, the Engineer

Arthur Clarke’s experiences during World War II and education in physics and mathematics made him well poised to make significant contributions in engineering after the war. In 1945, Clarke published his landmark scholarly paper “Extra-Terrestrial Relays – Can Rocket Stations Give World-wide Radio Coverage?” in the British magazine Wireless World (download PDF). In the paper, Clarke set out the first principles of global communication via satellites placed in geostationary orbits. A geostationary satellite orbits the Earth above the equator so that the period of the orbit (the time it takes the satellite to complete one orbit around the Earth) is the same as the Earth’s rotational period (the time it takes the Earth to rotate once around its axis.) This means that to an observer located on the surface of the Earth, the satellite appears not to move in the sky but stay at a fixed position. The idea of these kinds of orbits was originally proposed in 1928, but Clarke was the first to suggest that geostationary orbits would be ideal for establishing worldwide telecommunication relays. Since a satellite in a geostationary orbit does not appear to move in the sky, antennas on the ground do not have to track the satellite across the sky but can be pointed permanently to one location, which makes communications between ground stations and satellites easier.

Over the next decades, Clarke’s discovery evolved from his original, pre-computer era idea of using large, manned space stations to act as relays, to the small, unmanned, robotic telecommunications satellites used today. During this time, Clarke worked with scientists and engineers in the United States in the development of spacecraft and launch systems. After the launch of the Sputnik satellite by the Soviet Union in 1957, the discussion of the use of outer space by different nations of the Earth become an important global issue. Clarke was involved in these discussions by, e.g., addressing the United Nations during their deliberations on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. In the 1950s, Clarke started corresponding with Dr. Harry Wexler, the chief of the Scientific Services Division of the U.S. Weather Bureau, about satellite applications for weather forecasting. These discussions led to Dr. Wexler being the leading force behind a new branch of meteorology, where rockets and satellites were used for meteorological research and operations. Clarke saw his vision of global telecommunications via satellites start to become reality in 1964 with the launch of the first geostationary communication satellite Syncom 3, which was used to broadcast the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo to the United States. Today’s world relies so heavily on global satellite telecommunications networks that it would be difficult to imagine what the world would look like without them.

Arthur Clarke’s engineering work brought him numerous awards and honors, including the 1982 Marconi International Fellowship, a gold medal of the Franklin Institute, the Vikram Sarabhai Professorship of the Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, the Lindbergh Award, and a Fellowship of King’s College, London. Today, the geostationary orbit at 36,000 kilometers (22,000 miles) above the equator, which Clarke first described as useful for satellite communication relays, is named the Clarke Orbit by the International Astronomical Union.

Arthur C. Clarke, the Futurist

As important as Arthur Clarke’s achievements in engineering were to the modern world, he is at least as well known as a futurist, trying to predict what the world of tomorrow might look like, and as a popularizer of science, helping make science accessible to everyone. He is perhaps best known as a world-renowned science fiction writer, starting with the first story he sold professionally, “Rescue Party”, which was written in March 1945 and appeared in the magazine Astounding Science in May 1946. His body of work contains more than 70 books of fiction and non-fiction, and he received numerous awards for his writing.

Clarke’s most famous non-fiction work as a futurist may be the book Profiles of the Future, based on a series of essays he started writing in 1958 and published in book form in 1962. In the book he envisioned the probable shape of tomorrow’s world, including a timetable of possible inventions from the present to the year 2100. He often incorporated his visions of the technological advances in the near future into his science fiction writing. A prime example of this is his 1979 novel Fountains of Paradise, which describes the construction of a space elevator, a giant structure rising from the ground and linking with a satellite in a geostationary orbit. While concepts for various kinds of space elevators had been discussed for decades, Clarke helped bring the idea to the larger public consciousness and envisioned a future where the use of space elevators to lift payloads to orbit would make rocket launches obsolete.

Clarke strived to engage audiences in different media. In 1964, he started working with the noted film producer Stanley Kubrick on a science fiction movie script. The result of the collaboration was the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was released in 1968 and is widely recognized as one of the most influential films ever made. Clarke and Kubrick were nominated for the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award for the film. Clarke also wrote a novelization of the film; the resulting book, which is based on the early drafts of the film and differs from it in some ways, also came out in 1968. Clarke published a sequel, 2010: Odyssey Two, in 1982, and worked with director Peter Hyams on the movie version, which was released two years later. One of the notable aspects of this collaboration was the very advanced way (for the time) it was done: using a Kaypro computer and a modem to link Arthur Clarke in Sri Lanka and Peter Hyams in Los Angeles. This novel approach was described later in the book The Odyssey File – The Making of 2010.

Clarke worked for decades in television, bringing scientific and engineering achievements to people’s homes across the world. He worked alongside Walter Cronkite and Wally Schirra for the CBS coverage of the Apollo 12 and 15 space missions in the United States. His TV series Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World (1981), Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers (1984), and Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious Universe (1994) have been shown in many countries around the world. Clarke also contributed to other TV series about space, such as Walter Cronkite’s Universe series in 1981.

Arthur C. Clarke, the Humanist

Arthur Clarke was always interested in the future of human race, not only in terms of what that future might look like, technologically speaking, but also in terms of what kind of a world we, the current inhabitants of our home planet, would leave to the future generations. As a result, Clarke was always concerned about the relationship of the human race to the natural world around it.

An expression of Clarke’s interest in the interaction of humans with nature was his enthusiasm for scuba diving. Clarke’s undersea explorations connected the purely personal enjoyment of the activity to history of the areas he explored. For example, in 1956 he discovered the underwater ruins of the original Koneswaram temple in Trincomalee, Sri Lanka, during a scuba diving expedition with the photographer Mike Wilson.

Clarke was devoted to making sure the next generation would receive the best education possible. He not only influenced young minds through his writing but also worked in formal education. He served as the Chancellor of the Moratuwa University in Sri Lanka in 1979-2002 and as the first Chancellor of the International Space University in 1989-2004.

Clarke was concerned about global climate change and what effect it may have on the future of humanity. He always stressed the urgent need for humanity to move beyond the use of fossil fuels, which he considered one of our most self-destructive behaviors. Yet Clarke was always optimistic about the future of humanity; he firmly believed that technological achievements would solve our current problems and lead to a better and brighter future for the entire human race.

It is Clarke’s optimism for the future that made him an ideal spokesperson for the importance of people across the globe working together to solve the problems of today and create a better world for all of humanity. The organizations carrying Clarke’s name, from the Arthur C. Clarke Foundation to the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Science Education, are proud to continue Clarke’s legacy of inspiring the present and future generations of Earth, our home planet.

I’m sometimes asked how I would like to be remembered. I’ve had a diverse career as a writer, underwater explorer, space promoter and science populariser. Of all these, I want to be remembered most as a writer — one who entertained readers, and, hopefully, stretched their imagination as well.—Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur’s Work

Fiction

Across the Seas of Stars

Against the Fall of Night

Childhood’s End

City and the Stars

The Deep Range

Dolphin Island

Earthlight

Expedition to Earth

A Fall of Moondust

The Fountains of Paradise

From the Oceans, from the Stars

Ghosts from the Grand Banks

Glide Path

The Hammer of God

Imperial Earth

Islands in the Sky

The Lion of Comarre

The Lost Worlds of 2001

The Nine Billion Names of God

The Other Side of the Sky

Prelude to Mars

Prelude to Space

Reach for Tomorrow

Rendezvous with Rama

The Sands of Mars

The Sentinel

The Songs of Distant Earth

The Sentinel

Tales from the “White Hart”

Tales of Ten Worlds

2001: A Space Odyssey (With Stanley Kubrick)

2010: Odyssey Two

2061: Odyssey Three

3001: The Final Odyssey

The Wind from the Sun

Non-fiction

“Extraterrestrial Relays” in Wireless World

“Space Stations for Global Communications” in Wireless World

Ascent to Orbit: A Scientific Autobiography

Astounding days: A Science Fictional Autobiography

Boy Beneath the Sea

The Challenge of the Sea

The Challenge of the Spaceship

The Coast of Coral

The Coming of the Space Age (edited)

The Exploration of the Moon

The Exploration of Space

The First Five Fathoms

Going into Space

How the World Was One

Indian Ocean Adventure

Indian Ocean Treasure

Interplanetary Flight

The Making of a Moon

1984: Spring

Profiles of the Future

The Promise of Space

The Reefs of Taprobane

Report on Planet Three

Science Fiction Hall of fame, III (edited)

Three for Tomorrow (edited)

Time Probe (edited)

Treasure of the Great Reef

The View from Serendip

Voice Across the Sea

Voices from the Sky

Collaborative Works

With Simon Welfare and John Fairley: Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World; Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers

With the Astronauts: First on the Moon

With Robert Silverberg: Into Space

With Chesley Bonestell: Beyond Jupiter

With the Editors of Life: Man and Space

With Peter Hyams: The Odyssey File

With Gentry Lee: Cradle

With Gentry Lee: Rama 11

Sir Arthur’s Quotes

In the struggle for freedom of information, technology, not politics, will be the ultimate decider.

Every revolutionary idea seems to evoke three stages of reaction. They may be summed up by the phrases: (1) It’s completely impossible. (2) It’s possible, but it’s not worth doing. (3) I said it was a good idea all along.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

As our own species is in the process of proving, one cannot have superior science and inferior morals. The combination is unstable and self-destroying.

Human judges can show mercy. But against the laws of nature, there is no appeal.

I don’t pretend we have all the answers. But the questions are certainly worth thinking about.

It has yet to be proven that intelligence has any survival value.

It is not easy to see how the more extreme forms of nationalism can long survive when men have seen the Earth in its true perspective as a single small globe against the stars.

It may be that our role on this planet is not to worship God but to create him.

Our lifetime may be the last that will be lived out in a technological society.

Politicians should read science fiction, not westerns and detective stories.

I don’t believe in astrology; I’m a Sagittarius and we’re skeptical.

The best measure of a man’s honesty isn’t his income tax return. It’s the zero adjust on his bathroom scale.

The greatest tragedy in mankind’s entire history may be the hijacking of morality by religion.

The limits of the possible can only be defined by going beyond them into the impossible.

There is hopeful symbolism in the fact that flags do not wave in a vacuum.

This is the first age that’s ever paid much attention to the future, which is a little ironic since we may not have one.

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

The best proof that there’s intelligent life in outer space is the fact that it hasn’t come here.

We stand now at the turning point between two eras. Behind us is a past to which we can never return … The coming of the rocket brought to an end a million years of isolation … the childhood of our race was over and history as we know it began.

The fact that we have not yet found the slightest evidence for life — much less intelligence — beyond this Earth does not surprise or disappoint me in the least. Our technology must still be laughably primitive; we may well be like jungle savages listening for the throbbing of tom-toms, while the ether around them carries more words per second than they could utter in a lifetime.

Two possibilities exist: Either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.

The Information Age offers much to mankind, and I would like to think that we will rise to the challenges it presents. But it is vital to remember that information — in the sense of raw data — is not knowledge, that knowledge is not wisdom, and that wisdom is not foresight. But information is the first essential step to all of these.

There is hopeful symbolism in the fact that flags do not wave in a vacuum.

I can never look now at the Milky Way without wondering from which of those banked clouds of stars the emissaries are coming. If you will pardon so commonplace a simile, we have broken the glass of the fire alarm and have nothing to do but to wait. I do not think we will have to wait for long.

—The Sentinel, 1948

Yet now, as he roared across the night sky toward an unknown destiny, he found himself facing that bleak and ultimate question which so few men can answer to their satisfaction. What have I done with my life, he asked himself, that the world will be poorer if I leave it.

—Glide Path, 1963

Behind every man now alive stand thirty ghosts, for that is the ratio by which the dead outnumber the living.

—Foreword to 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968

One of the biggest roles of science fiction is to prepare people to accept the future without pain and to encourage a flexibility of mind. Politicians should read science fiction, not westerns and detective stories.

—The Making of Kubrick’s 2001, Jerome Agel, 1970

Any teacher that can be replaced by a machine should be!

—Electronic Tutors, 1980

The dinosaurs disappeared because they could not adapt to their changing environment. We shall disappear if we cannot adapt to an environment that now contains spaceships, computers — and thermonuclear weapons.

—The Collected Stories, 2000

The danger of asteroid or comet impact is one of the best reasons for getting into space … I’m very fond of quoting my friend Larry Niven: “The dinosaurs became extinct because they didn’t have a space program. And if we become extinct because we don’t have a space program, it’ll serve us right!”

—Meeting of the Minds : Buzz Aldrin Visits Arthur C. Clarke, Andrew Chaikin, 2001

SETI is probably the most important quest of our time, and it amazes me that governments and corporations are not supporting it sufficiently.

—Seti@Home, 2006

2001 was written in an age which now lies beyond one of the great divides in human history; we are sundered from it forever by the moment when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped out on to the Sea of Tranquility. Now history and fiction have become inexorably intertwined.

—Foreword to the Millennial Edition of 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1999

… we have a situation in which millions of vehicles, each a miracle of (often unnecessary) complication, are hurtling in all directions under the impulse of anything up to two hundred horsepower. Many of them are the size of small houses and contain a couple of tons of sophisticated alloys – yet often carry a single passenger. They can travel at a hundred miles an hour, but are lucky if they average forty. In one lifetime they have consumed more irreplaceable fuel than has been used in the whole previous history of mankind. The roads to support them, inadequate though they are, cost as much as a small war; the analogy is a good one, for the casualties are on the same scale.

—Profiles of the Future, 1972

For his 90th birthday in December 2007, Arthur C. Clarke recorded a greeting to his friends around the world. As part of the message, Clarke expressed three wishes:

Firstly, I would like to see some evidence of extra-terrestrial life. I have always believed that we are not alone in the universe. But we are still waiting for ET to call us — or give us some kind of a sign. We have no way of guessing when this might happen — I hope sooner rather than later!

Secondly, I would like to see us kick our current addiction to oil, and adopt clean energy sources. … Climate change has now added a new sense of urgency. Our civilisation depends on energy, but we can’t allow oil and coal to slowly bake our planet…

The third wish is one closer to home. I’ve been living in Sri Lanka for 50 years — and half that time, I’ve been a sad witness to the bitter conflict that divides my adopted country. I dearly wish to see lasting peace established in Sri Lanka as soon as possible.

In his 90th birthday message, Clarke also addressed his legacy:

I’m sometimes asked how I would like to be remembered. I’ve had a diverse career as a writer, underwater explorer, space promoter and science populariser. Of all these, I want to be remembered most as a writer — one who entertained readers, and, hopefully, stretched their imaginations as well.

From Profiles of the Future, 1973 Edition

Our age is in many ways unique, full of events and phenomena that never occurred before and can never happen again. They distort our thinking, making us believe that what is true now will be true forever, though perhaps on a larger scale. Because we have annihilated distance on this planet, we imagine that we can do it once again. The facts are otherwise, and we will see them more clearly if we forget the present and turn our minds towards the past.

When the pioneers and adventurers of our past left their homes in search of new lands, they said good-bye forever to the place of their birth and the companions of their youth. Only a lifetime ago, parents waved farewell to their emigrating children in the virtual certainty that they would never meet again. And now, within one incredible generation, all this has changed.

We have abolished space here on the little Earth; we can never abolish the space that yawns between the stars. Once again, as in the days when Homer sang, we are face-to-face with immensity and must accept its grandeur and terror, its inspiring possibilities and its dreadful restraints.

To obtain a mental picture of the distance to the nearest star, as compared with the distance to the nearest planet, you must imagine a world in which the closest object to you is only five feet away — and there is nothing else to see until you have traveled a thousand miles.

Space can be mapped and crossed and occupied without definable limit; but it can never be conquered. When our race has reached its ultimate achievements, and the stars themselves are scattered no more widely than the seed of Adam, even then we shall still be like ants crawling on the face of the Earth. The ants have covered the world, but have they conquered it — for what do their countless colonies know of it, or of each other? So it will be with us as we spread out from Mother Earth, loosening the bonds of kinship and understanding, hearing faint and belated rumors at second — or third — or thousandth hand of an ever-dwindling fraction of the entire human race. Though the Earth will try to keep in touch with her children, in the end all the efforts of her archivists and historians will be defeated by time and distance, and the sheer bulk of material. For the numbers of distinct human societies or nations, when our race is twice its present age, may be far greater than the total number of all the men who have ever lived up to the present time. We have left the realm of comprehension in our vain effort to grasp the scale of the universe; so it must always be, sooner rather than later.

Originally from the essay Space and the Spirit of Man, 1965

Verified in Greetings, Carbon-Based Bipeds!, Collected Essays 1934-1998, St. Martin’s Press 1999

We seldom stop to think that we are still creatures of the sea, able to leave it only because, from birth to

death, we wear the water-filled space suits of our skins.

…we cannot predict the new forces, powers, and discoveries that will be disclosed to us when we reach the other planets or can set up new laboratories in space. They are as much beyond our vision today as fire or electricity would be beyond the imagination of a fish.

The rash assertion that ‘God made man in His own image’ is ticking like a time bomb at the foundations of many faiths, and as the hierarchy of the universe is disclosed to us, we may have to recognize this chilling truth: if there are any gods whose chief concern is man, they cannot be very important gods.

From The Light of Other Days, by Arthur C. Clarke and Stephen Baxter, 2000

What we need is a machine that will let us see the other guy’s point of view.

Science demands patience.

What is becoming more interesting than the myths themselves has been the study of how the myths were constructed from sparse or unpromising facts—indeed, sometimes from no facts—in a kind of mute conspiracy of longing, very rarely under anybody’s conscious control.

Just as the human memory is not a passive recorder but a tool in the construction of the self, so history has never been a simple record of the past, but a means of shaping peoples.

The vendors seemed comical, so intent were they on their slivers of meaningless profit, all unaware of the desolate ages that lay in their own near future, their own imminent deaths.

Maybe those nihilist philosophers are right; maybe this is all we can expect of the universe, a relentless crushing of life and spirit, because the equilibrium state of the cosmos is death…

We always thought the living Earth was a thing of beauty. It isn’t. Life has had to learn to defend itself against the planet’s random geological savagery.